Saturday, February 27, 2016

Open Letter to Hattie McDaniel

In the Huffington Post, an open letter to Hattie McDaniel, the actress that played the mammy in Gone With the Wind and who played the role of maid 74 times. McDaniel was the first Black to win an Oscar in 1940 when she won for Best Supporting Actress. With all the discussion about this year's Oscars, the lack of diversity in the nominees, and the boycotting, an important read! (h/t Devon Pitts)

"When Whites are Guilty of Colorism"

Article in the Washington Post about two of the most common reasons Whites often overlook colorism.

Monday, February 22, 2016

American Girl Debuts New African American Doll from the Civil Rights Era

These new American Girl dolls are EVERY. THING.

This summer, American Girl is set to release a new historical doll, named Melody, the third African American doll in its BeForever historical line.

THEROOT.COM|BY BREANNA EDWARDS

Thursday, February 18, 2016

"How Privilege Lists Often Ignore the Intersection of Dis/Ability" by Cara Liebowitz

5 Examples of How Privilege Lists Often Ignore the Intersection of Dis/Ability

by Cara Liebowitz(Original source: http://everydayfeminism.com/2016/02/privilege-lists-and-disability/)

People often struggle with the concept of privilege.

And that’s understandable because, in essence, privilege means not having to think about privilege. And this can lead to trouble when those who are oppressed try to explain privilege and oppression: how do we start a conversation about something that isn’t even on someone’s radar?

Privilege checklists – which provide examples of privileges in an attempt to show you how you’ve been advantaged by society in ways you haven’t even considered – are a great introduction to the realities of privilege, especially for those who have never pondered the issue before.

They provide concrete examples of how privilege (and marginalization) affects our everyday lives. And as such, privilege checklists can sometimes be more helpful than trying to explain an -ism (whether it be racism, sexism, ableism, or another) on our own.

But while privilege checklists are a great “first look,” they fail to go deeper – and sometimes that can get in the way. For example, most privilege checklists fail to acknowledge intersectional oppressions, where two or more marginalized identities interact.

In particular, I’ve noticed that privilege checklists often fail to consider how disability impacts identities, and how disabled people who are marginalized in other ways (along the axes of race, gender, and so on) have a different experience of those marginalized identities due to ableism.

To give you an idea of what I mean by that, I looked at Buzzfeed’s “How Privileged Are You?”checklist for examples of how privilege checklists in general often fail to acknowledge the realities of dis/ability.

1. ‘I Have Never Been Catcalled’

Male privilege means that men can go out in public without being bombarded with derogatory sexual comments. This way in which women and other gender and sexual minorities are objectified and reduced to the sex appeal of their bodies is an example of rape culture.

However, when I saw this one, I paused.

Yes, it’s true that I’ve never been catcalled – but in my case, that’s not evidence of male privilege. I am most definitely a woman and present femininely.

Rather, I’ve never been catcalled because I am visibly disabled – so my body isn’t seen as sexually attractive.

My body evokes pity, rather than desire. I’m objectified and defined by my body, like people who are catcalled, but in a different way. My body (and extensions of my body, like my wheelchair) is touched and handled without my permission, not because I’m seen as a sexual commodity, but because I am seen as perpetually in need of “help” and salvation from able-bodied people.

So, the fact that I have never been catcalled is not so much evidence of privilege in one area, but evidence of disprivilege in another.

2. ‘I Have Never Done My Taxes Myself’

People who are class privileged can often pay someone else (or pay for software) to do their taxes for them. However, the fact that I’ve never done my taxes myself is not necessarily evidence of class privilege.

I’ve never done my taxes myself because I’ve never done my taxes. I’ve never made enough money to be taxed because I have never had a job that pays a steady wage.

This also ties into ability privilege and ableism, because disability is the main reason why I’ve never had a steady job. Disabled people as a whole have abysmally low employment, and disabled women even more so.

Unfortunately, disabled people who are class privileged are usually an exception, not a rule. It becomes even more complex when other identities, like race, are introduced into the mix.

I am not class privileged because I’ve never done my taxes myself. I am class disprivileged because I have never done my taxes at all.

3. ‘I Have Never Felt Poor’

This statement is problematic in and of itself because it’s incredibly subjective. That is, a lot of people “feel poor” in their lives. But that doesn’t necessarily mean that they’re not class privileged.

As a woman, I am likely to be paid less than a man, but I still am likely to get paid more than most women of color. As a disabled person, it is unlikely that I’ll be employed at all, yet disabled men are still more likely to be employed than disabled women.

The unemployment rate is more than doubled for people with disabilities versus people without disabilities. And many disabled workers get paid just pennies because of federal exemption to minimum wage laws.

Many disabled people are trapped in a cycle of poverty because of the way disability benefits like SSI and SSDI work.

SSI and SSDI are tied to Medicaid, which provides many disabled people with necessary personal assistant services. If you have over a certain amount of assets (including savings in bank accounts or cash, and valuables such as a car or house), your benefits get slashed and could eventually be cut altogether, leaving disabled people without personal assistants.

Because of this vicious cycle, even disabled people who could work with the reasonable accommodations more often than not are forced into unemployment in order to keep the services that very literally keep them alive.

The poverty cycle even influences who we marry. If a person on benefits marries someone who is not on benefits, they are considered dependent on their spouse and their benefits are cut, because the spouse’s income is taken into account.

If a person on benefits marries another person on benefits, their incomes will be taken together. Both people will have their benefits slashed if their combined income exceeds the resource limit. This is often referred to as the “marriage penalty.”

So classism is unfortunately closely related to ableism, and “feeling poor” is an unfortunate reality for a lot of disabled people.

Feeling poor and class privilege can also depend on the environment and location you’re in. As a child and teen, I felt poor many times, even though my family was solidly middle class, because we didn’t have as much money as some of my friends’ families.

Even though we weren’t privileged in relation to other people in our area, we were still privileged. We had enough money for food, clothes, rent, and two cars. Our basic necessities were always provided for. That’s a sign of privilege, even though it may not have felt like it at the time.

4. ‘I’ve Never Worked As a Server, Barista, Bartender, or Salesperson’

This is, again, a reference to class privilege.

The jobs mentioned generally pay very little (servers, in particular, mostly depend on tips) and employees must work long hours in order to make enough money to make ends meet. These are considered entry level jobs, which most people must work in order to gain access to higher jobs.

It’s the bootstraps mentality of capitalism: If you work hard at mediocre jobs, you have “paid your dues,” so to speak, and are granted access to better quality, higher paying jobs.

However, like the statement above about paying taxes, for me, this statement by necessity interacts with both class and able privilege.

I have never had any of those jobs because I’m physically incapable of doing most of them. My limited motor skills mean that most entry-level jobs – like folding clothes, working a cash register, and serving food – are off limits for me.

As a teenager, when most of my peers were getting their first jobs and getting used to the culture of employment, I was at home, depending on my parents for money.

I don’t have the skills necessary for the most basic of work. That severely limits my prospects for employment.

Ironically, because I can’t do entry-level jobs, I’m denied the upper-level jobs that I could actually do well.

5. ‘I Am Not Nervous in Airport Security Lines’

This is obviously a reference to (both real and perceived) race, ethnicity, and religion – and how people of color (especially those whose dress is racialized) are more likely to be pinpointed for extra screening and viewed as possible terrorists.

People who are brown, black, and/or wear religious garb, especially Muslims, are regarded with suspicion on the streets and in our presidential campaigns. And when it comes to the security of our country, the racism and Islamophobia is even more blatant.

Just a few days ago, a prominent Australian politician, the first Muslim member of Australian Parliament, was interrogated by the TSA at LAX airport, who implied that her Australian passport was stolen. People of color, especially those who wear religious garb, have good reason to be nervous in airport security lines.

However, even though I’m a white woman, I’m still very nervous in airport security lines – not because of my race, but because of my disability.

When I’m in airport security lines, I have two choices: either walk through the security scanner, causing panic that a woman using a wheelchair can get up and not immediately fall on her face and leaving my wheelchair to be manhandled by the TSA, or stay in my chair and get patted down, which means that there’s a chance I may be touched in areas that are uncomfortable or cause pain.

I’m often nervous that my expensive mobility aids will be damaged in the course of security, leaving me effectively stranded.

Flying in general makes me nervous because of these reasons, and hardly a day passes when I don’t hear about another friend whose wheelchair or other mobility aid got damaged because of poor handling in airports.

I may not be nervous in airport security lines because of my race, and that’s a privilege I have that I recognize. But I am nervous in airport security lines because of my disability – and that is equally valid.

***

Privilege lists, while very useful, often fail to convey the nuance of privilege and present privilege as a black-and-white phenomenon, when that’s not the case at all. You can be privileged and disprivileged in shades, and that’s not necessarily quantifiable.

Perhaps most importantly, as a disabled person, my privileges and disprivileges are all inseparably linked to my disability.

Because most people aren’t knowledgeable about the issues that affect people with disabilities, it is generally assumed that disability only affects disability issues, when disability can affect race, class, gender, and all strata of privilege and oppression. This is why single-issue privilege lists can be problematic.

Activist Mia Mingus, who is a disabled woman of color, argues that ableism intersects with all oppression, privilege, and justice. She says:

“Ableism must be included in our analysis of oppression and in our conversations about violence, responses to violence and ending violence. Ableism cuts across all of our movements because ableism dictates how bodies should function against a mythical norm—an able-bodied standard of white supremacy, heterosexism, sexism, economic exploitation, moral/religious beliefs, age and ability.”

If we do not acknowledge how disability intersects with other identities, and how disability can impact privilege, we’re perpetuating the continual erasure of ableism from discussions of oppression and privilege.

Most people have heard of sexism and racism, and acknowledge that those oppressions exist. However, more than once, I’ve been told that the concept of ableism as disability oppression is “ridiculous,” that people have “never heard of it,” and that it doesn’t exist.

I’m not disparaging privilege lists at all. I think they’re a great tool to get people thinking about how privilege affects their everyday lives. But it’s just a start. It’s basic. And we can’t mistake basic information for a complex education.

Cara Liebowitz is a Contributing Writer for Everyday Feminism. She is a multiply-disabled activist and writer currently pursuing her M.A in Disability Studies at the CUNY School of Professional Studies in Manhattan. Her published work includes pieces in Empowering Leadership: A Systems Change Guide for Autistic College Students and Those with Other Disabilities, published by the Autistic Self Advocacy Network, and the Criptiques anthology. Cara blogs about disability issues large and small at That Crazy Crippled Chick. You can check her out on Twitter @spazgirl11.

"Trigger Warnings, the Big Picture: Changing Our Culture of Social Control"

To continue the end of/after class discussion about trigger warnings on 2/17/16:

Trigger Warnings, the Big Picture: Changing Our Culture of Social Control

Jay Livingston, PhD on July 22, 2015

Recently there’s been heightened attention to calling out microaggressions and giving trigger warnings. I recently speculated that the loudest voices making these demands come from people in categories that have gained in power but are still not dominant, notably women at elite universities. What they’re saying in part is, “We don’t have to take this shit anymore.” Or as Bradley Campbell and Jason Manning put it in a recently in The Chronicle:

…offenses against historically disadvantaged social groups have become more taboo precisely because different groups are now more equal than in the past.

It’s nice to have one’s hunches seconded by scholars who have given the issue much more thought.

Campbell and Manning make the context even broader. The new “plague of hypersensitivity” (as sociologist Todd Gitlin called it) isn’t just about a shift in power, but a wider cultural transformation from a “culture of dignity” to a “culture of victimhood.” More specifically, the aspect of culture they are talking about is social control. How do you get other people to stop doing things you don’t want them to do – or not do them in the first place?

In a “culture of honor,” you take direct action against the offender. Where you stand in society – the rights and privileges that others accord you – is all about personal reputation (at least for men). “One must respond aggressively to insults, aggressions, and challenges or lose honor.” The culture of honor arises where the state is weak or is concerned with justice only for some (the elite). So the person whose reputation and honor are at stake must rely on his own devices (devices like duelling pistols). Or in his pursuit of personal justice, he may enlist the aid of kin or a personalized state-substitute like Don Corleone.

In more evolved societies with a more extensive state, honor gives way to “dignity.”

The prevailing culture in the modern West is one whose moral code is nearly the exact opposite of that of an honor culture. Rather than honor, a status based primarily on public opinion, people are said to have dignity, a kind of inherent worth that cannot be alienated by others. Dignity exists independently of what others think, so a culture of dignity is one in which public reputation is less important. Insults might provoke offense, but they no longer have the same importance as a way of establishing or destroying a reputation for bravery. It is even commendable to have “thick skin” that allows one to shrug off slights and even serious insults, and in a dignity-based society parents might teach children some version of “sticks and stones may break my bones, but words will never hurt me” – an idea that would be alien in a culture of honor.

The new “culture of victimhood” has a different goal – cultural change. Culture is, after all, a set of ideas that is shared, usually so widely shared as to be taken for granted. The microaggression debate is about insult, and one of the crucial cultural ideas at stake is how the insulted person should react. In the culture of honor, he must seek personal retribution. In doing so, of course, he is admitting that the insult did in fact sting. The culture of dignity also focuses on the character of offended people, but here they must pretend that the insult had no personal impact. They must maintain a Jackie-Robinson-like stoicism even in the face of gross insults and hope that others will rise to their defense. For smaller insults, say Campbell and Manning, the dignity culture “would likely counsel either confronting the offender directly to discuss the issue,” which still keeps things at a personal level, “or better yet, ignoring the remarks altogether.”

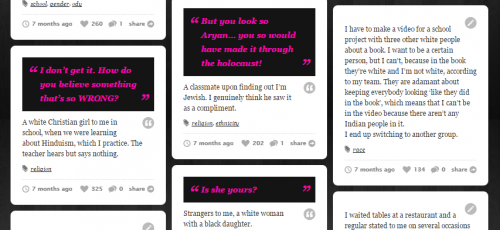

In the culture of victimhood, the victim’s goal is to make the personal political. “It’s not just about me…” Victims and their supporters are moral entrepreneurs. They want to change the norms so that insults and injustices once deemed minor are now seen as deviant. They want to define deviance up. That, for example, is the primary point of efforts like the Microaggressions Project, which describes microaggressions in exactly these terms, saying that microaggression “reminds us of the ways in which we and people like us continue to be excluded and oppressed” (my emphasis).

So, what we are seeing may be a conflict between two cultures of social control: dignity and victimhood. It’s not clear how it will develop. I would expect that those who enjoy the benefits of the status quo and none of its drawbacks will be most likely to resist the change demanded by a culture of victimhood. It may depend on whether shifts in the distribution of social power continue to give previously more marginalized groups a louder and louder voice.

Cross-posted at Montclair SocioBlog.

Jay Livingston is the chair of the Sociology Department at Montclair State University. You can follow him at Montclair SocioBlog or on Twitter.

Mixed marriages are changing the way we think about our race

According to a recent article in the Washington Post, "The report from Duncan and Trejo has two major consequences. First, it casts some doubt on the government's projections of the future Hispanic and Asian populations. Famously, the Census Bureau has predicted that non-Hispanic whites will become outnumbered in America by as early as 2044. But as Pew has pointed out, these calculations don’t take into account trends in how the children of mixed marriages report their own race. A fair fraction of people with Asian or Hispanic heritage actually consider themselves exclusively white (or black)."

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)